The Longevity of The Runfluencer

Running brands look towards influencers to drive impressions and sell product. But how long of a runway do influencers really have?

Imagine you’re an influencer who picked up running a few years ago. The sport is fresh and new and the possibilities are endless. As your social following grows, your times get faster, your workouts become more dialed, and maybe you’re invited to run TSP (you’re in it now). Running has opened doors you never thought possible.

Then reality hits.

You encounter your first major injury. For those of us who’ve been running since high school, we know this is inevitable (personally I’ve dealt with two fractured metatarsals, a partially torn hamstring, and a torn plantar–and that’s just my short list). Running injuries are the absolute worst, and I completely empathize with anyone struggling to receive a diagnosis or experiencing setbacks.

For the running influencer who’s built an empire off sharing every aspect of their training, it’s an awkward predicament. It means the content they create must be altered, and it sends many influencers spiraling when they can’t monetize their participation in the sport on social media as intended.

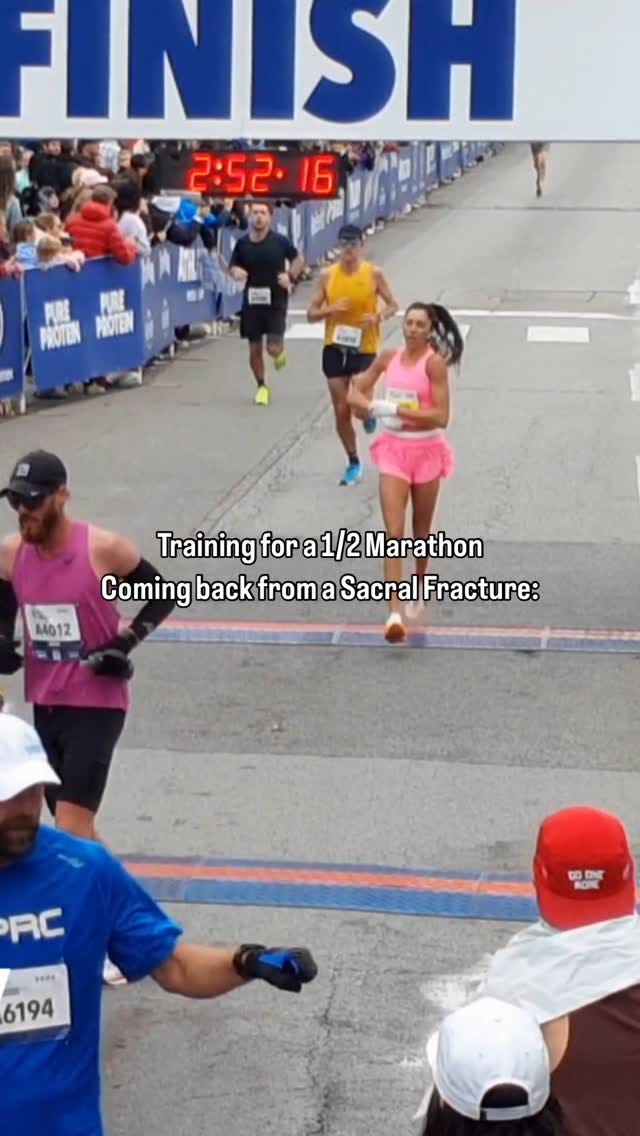

Of course, you can always create a beautiful narrative about a comeback. Healing from an injury is relatable. After all, 75% of runners get injured on a yearly basis. Just ask Caitlyn Miller (@caitlynmiller_fit), 2:52 marathoner who experienced a sacral stress fracture in December, 2024. I worked with Caitlyn when I managed athlete marketing at COROS, and she developed her injury around the time I left. Caitlyn had a number of brand partnerships and activations lined up for the Boston Marathon, but unfortunately couldn’t run and had to deliver the news not only to brands she worked with, but also to her 147,000 followers.

“I treated this as a way of telling a story about an injury–how I’m going to overcome it and what I’m doing to do about it,” she explained. “I won’t lie, I wish it didn’t happen. When it affects your mental health, it affects your output. It was something I had to get creative with. I had to view it as an opportunity to tell maybe not the story I wanted to tell, but a different story that could be just as impactful.”

Despite not running Boston, Caitlyn was able to pivot, learn some hard lessons about training and recovery, and will now be running Grandma’s Half in June. She’s used the downtime to rehab her body, optimize her nutrition and training, and recently made the difficult decision to move back to Florida so she can train at sea level, which is better for her body, and so she can enjoy the warm, humid weather.

Caitlyn is one of many “runfluencers” who have recently battled injuries. Ultimately, it’s how a running influencer chooses to handle setbacks and tell their stories that will set them apart in the space. Too often, we see people running through injury, doing back to back races, and taking a Goggins-esque approach to powering through workouts. Many creators can come across as frantic and desperate as they obsessively cross-train and ignore advice from medical professionals. While it looks inspiring on the surface, it has dangerous consequences that followers may not be privy to.

Where Do Running Influencers See Themselves in 10, 20 Years?

Injuries will always be something runners deal with, whether you’re a seasoned pro athlete or a beginner. Building an online brand and maintaining authority as a content creator, however, is less predictable.

Where do creators see themselves in 10 years? This is a question I’ve asked myself too, when it comes to my online social media presence. When I’m 60, will I still have photos of myself in a bikini from 30 years ago on my grid? We’re all aging in real time, while our digital footprint remains frozen in pixelated timestamps. Luckily for me, I don’t rely on social media for income. So where does that leave content creators who constantly have to reinvent themselves to stay relevant in the industry?

The longevity of the running influencer is pretty short unless they’ve built a really solid foundation that provides education (product reviews, coaching advice), community impact, or deep storytelling. Brands will typically only sign quarterly or yearly agreements with an influencer, or they’re paying per post, which means that most influencers are cycling through partners to pay the bills. Brands are also playing hopscotch and will partner with whatever influencer is on the rise as they try to capture the latest trends and viral moments. To note, we are seeing more brands like HOKA and On sign multi-year deals with ambassadors (instead of pro athletes) to create consistency instead of one-off influencer posts.

We’re all aging in real time, while our digital footprint remains frozen in pixelated timestamps.

When we talk about professional athletes, the standard is a 4-year shoe deal, which includes at least one Olympic cycle. Renewals are typically based on performance and the athlete’s desire to continue competing. At some point, the professional athlete will retire and either get a multi-year contract announcing for track events on NBC, or fade into obscurity as they create a normal life for themselves with a family and a real estate license.

But what does “retirement” look like for the running influencer? When you’ve intentionally built a brand and an identity on social media, how do you disengage from that when it no longer serves you, or when people stop paying attention?

“I think one thing that I find comforting is that I do have my own company,” says Caitlyn. “Ten years down the road I would hope to be more established with that. I love content creation and I love running, but I have long-term goals beyond showing it to social media.”

For a popular influencer, I feel the exit strategy can go 1 of 2 ways. You either pivot gracefully without making a huge deal about it and use your savvy digital marketing skills to excel in a new space (like working in-house, starting your own brand, or becoming a consultant), or you desperately cling on to internet “fame” as you are forced to reinvent yourself and exhaust every media channel possible. You might also recycle old content and post the same photos over and over again because you’re running out of things to talk about.

When you’ve built a brand and an identity on social media, how do you disengage from that when it no longer serves you, or when people stop paying attention?

There are many running influencers who’ve had a viral moment that got them a lot of followers, but years have gone by and they’ve struggled to redefine who they are. Kelly Roberts comes to mind. Her “Run, Selfie, Repeat” moment was empowering back in 2016, but over time her content became increasingly desperate and disjointed from my perspective. She’s been called out by Marathon Investigation for ignoring rules and banditing races, while advocating for body positivity while shaming those who have a physique she deems fitter or skinnier than hers. While her intentions are good (empowering women, promoting inclusivity), it’s hard to decipher what she does now, and that can be tricky for brands looking for a certain POV. It’s also a red flag when someone has over 100k followers, but gets less than 100 likes on a post.

For many running influencers who experienced viral fame, there seems to be a need to capitalize on every outlet to stay relevant–podcasts, YouTube, merch, a run club–without a real strategy in place. These things are created out of thin air with minimal purpose or voice behind it. We see this in popular culture too, notably Hailey “Hawk Tuah” Welch who, for reasons I cannot begin to understand, has a podcast where she talks about nothing, as well as her very own cryptocurrency.

The Kelly Roberts case study is an example of how running influencers can become hugely popular and reach a lot of people in a positive way, but at some point brands will move on and new influencers will replace them. It also begs the question–when does someone stop being an influencer? What happens to their channels?

Unless you are constantly reinventing yourself in a way that’s relatable, trendy, and not desperate, you risk becoming irrelevant. It’s a tough space, and you need thick skin to survive.

Surviving The Internet Mob–What Does It Take to Get Canceled?

When you’re chronically posting your life online, you are signing up for criticism.

However, it seems like for a running influencer to get canceled, it has to be really bad. As long as you’re producing engaging content, you can get away with a lot. Time and time again, we’ve seen running influencers get publicly shamed for questionable behavior, but a few weeks later it’s like it never happened and they’ve signed a new brand deal. While I don’t believe in cancel culture, I do believe in accountability.

I hate to use the Matt Choi example because it’s trite and he’s genuinely a nice guy who apologized for his running wrongdoings, but it’s still the gold standard for what not to do as a running influencer. Don’t bandit, don’t bring e-bikes on the course, and don’t bring film crews on the Leadville segments where they’re not allowed. He’s broken all the unspoken rules of running and is literally banned from NYRR races, but his channel continues to grow because he makes engaging content.

Last month, Kate Mackz interviewed Karoline Leavitt, which felt very off-brand since they didn’t even go for a run. A lot of people were upset given the current political climate, and many people said they were unfollowing her page. But if you visit her profile, it’s business as usual and she still has 200k+ followers. She never addressed the very poignant questions people were asking: Did the White House pay for that interview? If so, is that propaganda?

The internet can be a cruel place where the mob attacks, but people move on and forget. And that’s good for influencers, but probably bad for society’s moral compass.

It seems that influencers can get away with pretty much anything these days, even being sued and cited in a wrongful death case. I’m referring to Eli Wehbe, the former LA nightclub owner who texted “Coke dealer can bang her. He gets the scum.” in reference to Kim Fattorini, the Playboy model who died of a GHB overdose after leaving his home unsupervised. Like many ultrarunner influencers, he’s #sober and has replaced his toxic lifestyle with high mileage as an act of penance. While he was never convicted of anything, I hesitate to give attention to someone like Eli who partied frequently with Dan Bilzerian and has documented news coverage of that fateful night.

The internet can be a cruel place where the mob attacks, but people move on and forget. And that’s good for influencers, but probably bad for society’s moral compass.

Dogs And Ai: The New Frontier Of Influencers

Not too long ago, ASICS announced their latest brand ambassador: Felix the Samoyed (@wanderlust_samoyed). While I saw this as an adorable, fun move for ASICS, it also signaled to me that brands recognize the need to play it safe. Sponsoring a dog avoids politics and controversial training advice, and I can’t think of one negative thing to say about a cute animal wearing sunglasses with the caption “Greetings from the beach 🏖️😍”.

Terminally online people like myself will also remember Lil Miquela, the original Ai influencer who appeared on Instagram before people even thought that was possible. She’s still thriving and has millions of followers. She’s done social collabs to promote environmental sustainability, she’s (virtually) attended court side NBA playoff games, and she’s promoted small businesses like minority-owned hair salons in Los Angeles. She hasn't received any hate or been canceled, as far as I can tell.

For brands spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on influencer marketing, I predict we’ll see more collabs with more neutral creators, including meme accounts, digital artists, and accounts dedicated to curated aesthetics (think Mental Athletic). It’s an exploratory market that allows companies to own the narrative a bit more and play with new forms of storytelling that don’t rely on a person’s well-being.

Final Advice For Running Influencers

Hone in on your niche. The saying in journalism is that broad generalizations lose an audience, while getting extremely specific with facts and research connects with more people. I apply this same logic to all content creation. I see a lot of creators bouncing from one fitness trend to the next (one weekend it’s Hyrox, the next weekend it’s the BPN Backyard Ultra). This isn’t sustainable and it can dilute your brand.

Specialize in 1-3 media channels. As I noted earlier, you don’t need to have a podcast, a merch store, a YouTube channel, a newsletter, a coaching business, and a speaking tour. When you’re doing all of these things at once without a real strategy, you risk spreading your message too thin and losing the plot.

Prioritize self-care. I am genuinely worried for some content creators out there who are having full mental breakdowns online when something goes wrong. At a certain point, watching people cry on their Instagram story and talk about throwing up multiple times during a race isn’t vulnerable anymore–it’s just there for shock value. Influencers who take care of their bodies and their mental health will inevitably see greater success forming long-term partnerships, since brands don’t want to risk having their content be affiliated with unhinged behavior.

Avoid trends for the sake of being trendy. I love a good trending TikTok audio. But there’s a difference in hopping on the trend bandwagon versus participating because you have a valuable POV. This also goes for racing. Just because you ran a marathon doesn’t mean you need to sign up for Cocodona 250.

Nurture your existing following instead of worrying about growth. When chatting with Caitlyn, she told me this is the #1 advice she’d offer creators. By interacting with your current audience and making them feel heard and valued, you’ll grow as a byproduct as people refer and share your content.

Great post. One thing that’s held me back is the longevity factor—and just how saturated the fitness influencer space has become. How many more takes do people really need on eating carbs or how to lift? Then it turns into a race to one-up each other with Ironmans and extreme challenges. I’ve decided to try carving out a space here on Substack that feels more grounded—less about catchy content, more about something real.

The injury rates in runfluencers seems higher than normal; I don't think it's that they don't know what they're doing, I think that it's the drive for great content means more running which leads to injuries.